Lumber Stamps!

Old houses are filled with treasure. Sometimes, that treasure takes the form of old letters, photographs, newspapers and other odds and ends that attest to the human presence that once filled a home. In the salvage world, the bounty is in the building materials themselves, the wood, brick, and stone that spent generations as parts of a house.

Occasionally, the treasure occupies both categories, and that is what we are concerned with today. Behold the scrawled name of Heise & Bruns, a lumber company that operated in our fair city from the 1860s to the 1920s, and the stamp of William Applegarth & Son, a shipping and commission house incorporated in 1850.

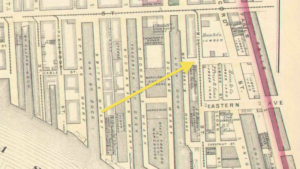

First, let’s examine Heise & Bruns. The firm was started by German immigrants William Heise and John Bruns in 1862. Their offices and yard were at the intersection of Concord and Eastern Avenues.

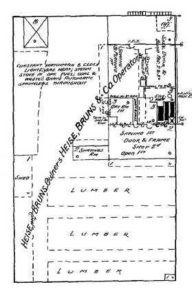

The yard was the largest in Baltimore, occupying 30,000 square feet, with room for one million board feet of lumber. As you can see in the schematic below, from old Sanborn insurance maps, at Heise & Bruns, they did it all: in addition to fulfilling the raw lumber needs of a growing city, the firm produced doors, windows, trim, lath and shingles.

In “Baltimore, Gateway to the South, Liverpool of America,” a monograph from 1898 extolling the virtues of a bustling city, the authors were kind enough to note that “Mr. Heise is one of Baltimore’s progressive and enterprising younger business men, and the firm as a whole, are gentlemen of that leading and public-spririted class which is accomplishing most towards keeping our city at the front in trade and commerce and bringing its resources and advantages most prominently to the attention of the country at large.”

William Applegarth & Son made their money operating ships up and down the Atlantic Coast. William was from a prominent Maryland family; he quickly moved from captaining ships to owning them, and eventually he became a master broker, overseeing a sizable fleet. In 1860, the value of William Applegarth’s real estate was listed as $13,000, while his personal wealth was estimated at $10,000. In addition to ferrying loads of salt from the Caribbean and granite from Port Deposit, the Applegarth concern sent schooners up the Susquehanna towards the rapidly denuding pine forests of Pennsylvania. The image below, from the Pennsylvania Lumber Museum, shows how the tall stands of Eastern White Pines that flourished in much of the state were clearcut, yielding boatloads (literally) of valuable lumber that made its way to cities across the Midwest and East Coast.

William died in 1873, but his sons Nathaniel and Thomas operated the company long after his passing out of their offices at 507 E Pratt, just down the street from the Heise & Bruns lumberyard. It seems likely that our joist was stamped by the Applegarths as cargo, then painted with the Heise & Bruns name once it had been taken into inventory, or perhaps once it was being ready to be sent to a builder. After the joist had been set in its pocket, it would have had lath and plaster applied to its bottom and floorboards nailed into its top; strip by strip, board by board, the names on the joists would have been obscured as the piece of wood completed the journey from raw material, to usable lumber, to an invisible structural member of a Baltimore rowhouse.